Books about Critical Race Theory (CRT) that target children as the audience are finding their way into schools and libraries across our country. An example of this was brought the attention of the Oakwood Community for Strong Schools when “This Book is Anti-Racist,” by Tiffany Jewel, was found recently in a 6th grade classroom in the district. “This Book is Anti-Racist” is a perfect example of the genre of books written to promote the beliefs of CRT among our unsuspecting youth in schools, all under the radar of trusting parents. Ultimately the term anti-racism is just a code word for critical race theory, as can be seen by the subject matter of the book and shown in the rest of the article below. You can find a primer on CRT on our page, Critical Race Theory Defined. While it appears that this book is not part of the core curriculum, it was made available to 11 and 12 year old children for private reading in class or at home.

Anti-racism in this book is defined as both being opposed to racism and actively working against racism (as defined later in the book). A key component of CRT is the promotion of activism among adherents, and activists are especially interested in our children. This activist component is especially corrosive to a learning environment, as it undermines the free exchange of ideas and the ability of students and staff to dive more deeply into the nuance of historical subjects. The CRT worldview requires that all of history be posed in terms of power and who controls it.

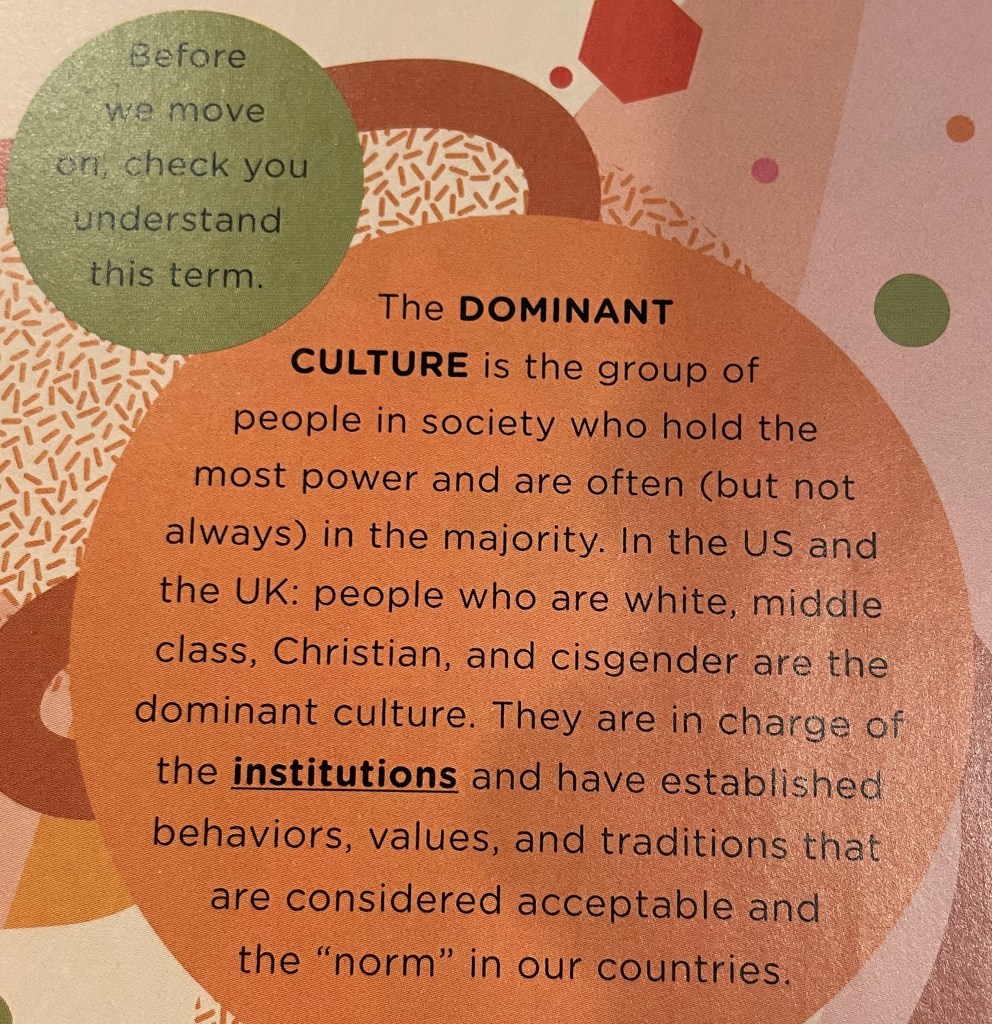

Chapter 1, “Who Am I,” introduces the idea of identity by identifying groups seen as the “dominant culture,” such as white, “cisgender,” “educated,” and “neurotypical” people. It is noted that these privileged individuals enjoy the benefits of the culture, as opposed to “subordinate culture,” such as blacks, queer, transgender, nonbinary, and neurodiverse individuals, among several specified in the text. The dichotomy of a normal/dominant culture versus the subordinate culture is a key tenet of CRT, derived from Marxist theories about the bourgeoisie and proletariat classes. As such, the book notes that “the dominant culture is the group of people in society who hold the most power.” As noted, this focus on power dynamics is also a key belief of CRT and Marxism.

Chapter 2 brings additional discussion of social identities and introduces a discussion of privilege and intersectionality. It highlights Kimberle Crenshaw, a CRT proponent who first developed and promoted intersectionality as a concept that highlights layers of oppression based upon the social groups to which you belong. The idea is that if you belong to multiple “marginalized” groups, you will experience a unique and more severe degree of oppression. A concern that many parents have is that these ideas remove personal accountability as an individual can attribute their place in life to the hierarchy of oppression and society in general. This undermines the idea of the American Dream, where hard work can allow any citizen of America to do well for themselves.

The next few chapters explore topics such as institutional power, systemic racism, and similar topics. All of these are key elements of CRT. Readers are encouraged to “notice who has power,” and to identify the “race of each of these folx,” and to see if they reflect the student or the “dominant culture.” Historical and modern topics from education to medical care are all discussed in a framework of race, highlighting perceived grievances for the reader.

Chapter 6 introduces additional topics like microaggressions, which serve to hypersensitize the reader to perceived slights, and to read them through a racial or queer lens. The author encourages the reader to carry a notebook and write down microaggressions that are witnessed throughout the day. All of this is chalked up to prejudice, regardless of intent or any other consideration, and serves to radicalize young people.

The next few chapters contain a survey of history through a lens of historical oppression, with colonial powers highlighted as the oppressors of BIPoC people through their use of institutional power. These chapters view every piece of history through a racial lens, encouraging the young reader to view history in the same way.

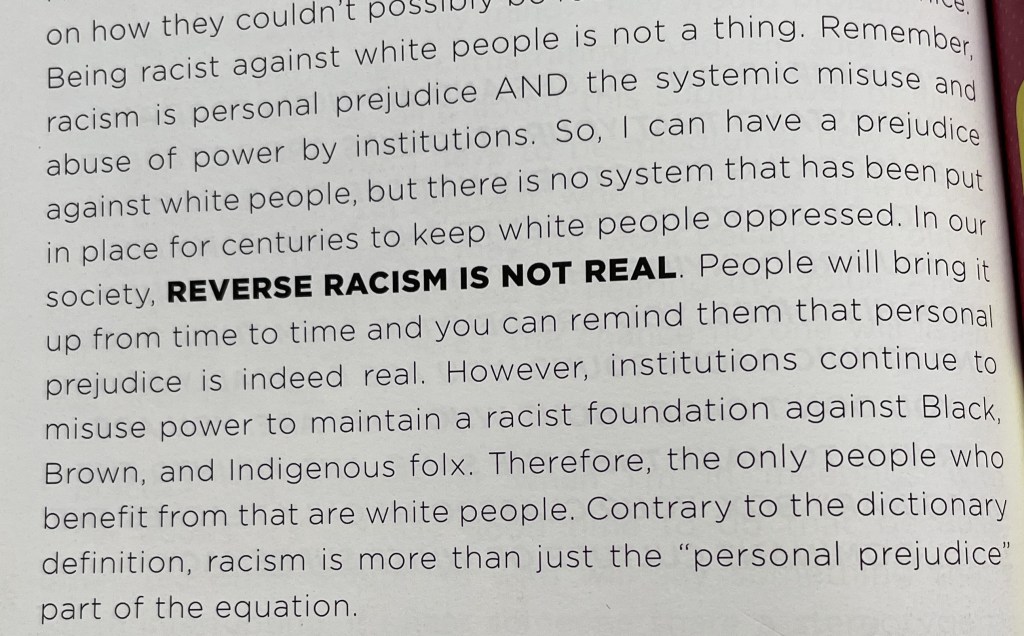

All of this is meant to motivate the activism laid out in chapters 10-14. In Chapter 10, children as young as 9 are encouraged to “Disrupt,” by speaking up and speaking truth to power. This may be disruption in a classroom if the child perceives some sort of injustice based on race or another political issue. The author also encourages the reader to stop to record and harass police if he or she sees a stopped car. White children are encouraged to do this as they have privilege and must show themselves to be allies. The reader is also told that staying silent is not an acceptable option. The next chapter encourages the reader to interrupt class or other situations when alleged microaggressions are witnessed or a discussion is being held that does not align with the anti-racist belief system. This disruption and interruption is “necessary” to push back upon the “institutions” enforcing systemic oppression. On page 102, the author states that she is permitted to hold prejudice against white people because “reverse racism is not real.” The author’s whole worldview revolves around categorizing people by race and pursuing preferential treatment for colored people. The final chapter in this section of the book discusses times to “call in” or “call out” someone who has said something the author defines as racist or a microaggression. Calling in is to speak to someone privately, while calling out is to speak about an issue in public, especially important when speaking against a “systemic power.” The act of “calling out” typically involves public accusations that undermine the moral authority of the accused, and in many ways amounts to a form of political bullying. This book is training children to bully other children over their political views – is this really what we want in our schools.

The book wraps up with chapters on topics like spending your privilege and allyship. The focus of these sections is encouraging the reader to consider where they sit on the intersectional pyramid and to use what power they have to advocate for others or to step aside as an ally and let BIPoC people speak or take positions of power. The work of anti-racism never ends!

This book is an excellent example of the beliefs of Critical Race Theory. Presented for our children is a lens to understand our history through a Marxist based racial or queer perspective that serves to radicalize the reader and create a lifelong activist. This type of material is entirely inappropriate for children who are not developmentally prepared to be exposed to these ideas in elementary school. While not incorporated into the curriculum, this book was available for children interested in reading material in their 6th grade classroom. Have you seen other books that would cause concern? Please let us know by sending a note to admin@oakwoodstrongschools.com.